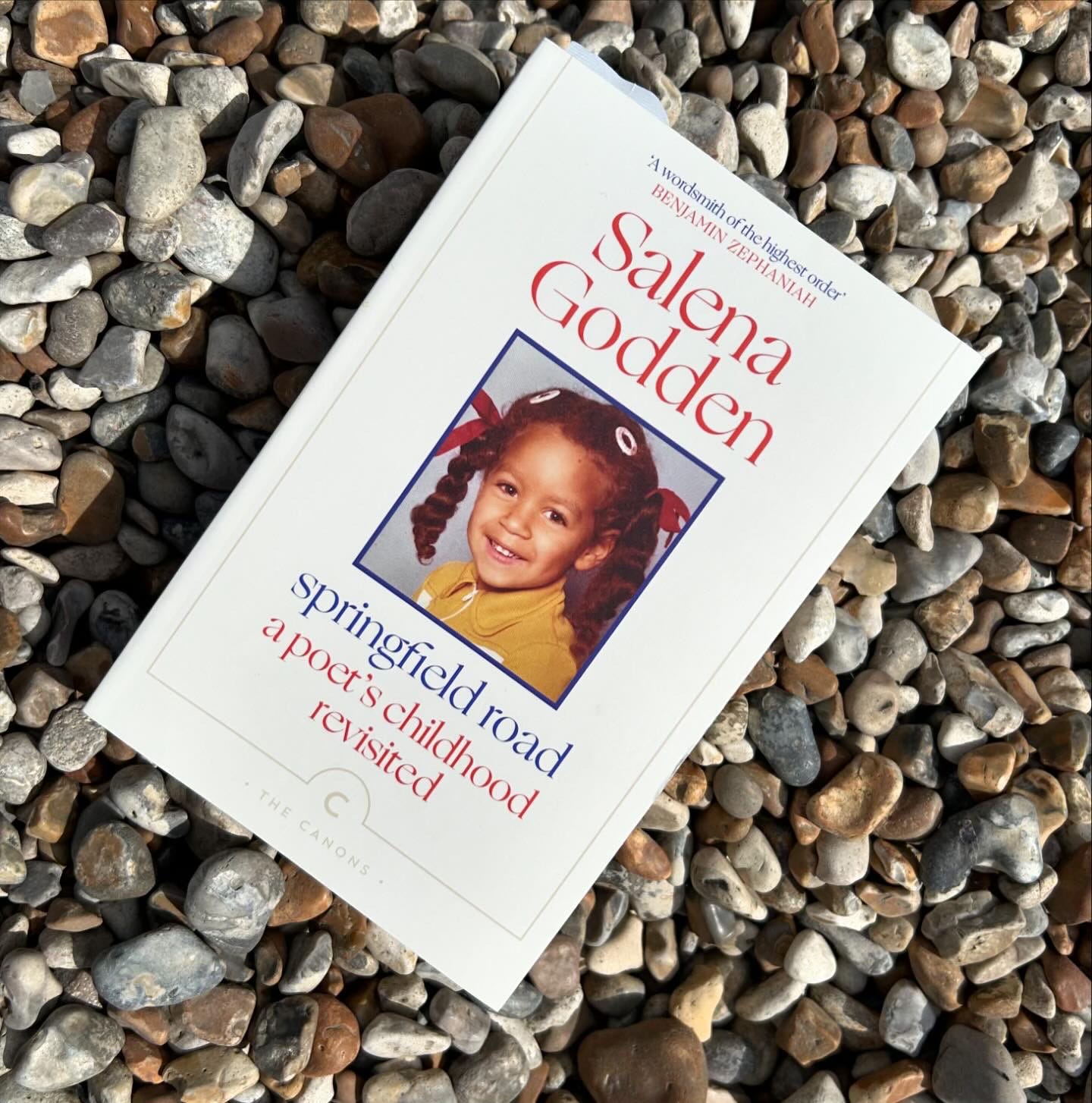

I am inspired to share some of my memoir Springfield Road with you today.

Earlier this month I was invited to speak about my books at ALSO Festival and I loved both of my shows. The With Love, Grief and Fury poetry set was on a stage in the forest, it was such a magical sunset gig, we were surrounded by ancient trees, the leaves whispering poetry back to us. Then for my memoir event the next day, we sat together on the lake stage on a gloriously warm and sunny Sunday morning and talked about Springfield Road and the process of writing this memoir and the women in the heart this book.

Thank you so much to Ben Pester who asked all the right questions and gave such a brilliant and generous interview. I’m so grateful for the opportunity and space to share my book in this way and to speak about the inspirational women in my life. To be honest, in almost every interview I have ever done with this memoir, the focus has been on the darkness and loss and the males in my family. So I was delighted that Ben and I talked about the women. The story of my mother and grandmother taking a boat from Jamaica to arrive at Dover to start a new life in strange country, the story of my father’s mother Edith adopting my father aged thirty-five and alone and unwed.

I know now that these women are the reason I wrote the book, the heart of the story. I felt like my grandmothers spirits were there with us on that stage, dancing in the soft July light, with the dragonflies and butterflies. Since this show at ALSO I keep thinking about our conversation, this deep dive into the women in the memoir, so here’s some thoughts here, just so I don’t forget and also to note and celebrate that. I will also share the piece from the memoir we discussed in such great detail, the chapter titled, The Heart Of Springfield Road.

image: black and white photo of my mum and dad, Springfield Road

At the heart of my debut novel, Mrs Death Misses Death, you will find recurring themes of survival and how women survive in a world that often doesn’t seem to want them to. It is probably no surprise that at the heart of my memoir, my childhood and family tree, there are women of fire, of remarkable courage and kindness that made an everlasting impression on me. I feel like I come from generous and resourceful women. Women that constantly had to re-think and re-invent and make-do to survive.

I was brought up to be independent, to hold my own. I was taught this mostly by my mother and by my grandmother, who knew what happens when the world tries to erase, squash or shush you. From my earliest years I feel like I was filled with their resilience. They told me that it is a tough world, hard world, and how to seek the light in it. I’m just a poet, but even in my line of work, it’s exhausting how thick-skinned we must be, just to survive, just to keep afloat, how our truth, empathy and vulnerability often feels risky, but it is somehow worth it, and we do it, find the softness, find the courage, keep blowing on the flames of hope, keep on keeping on, don’t we…

Let’s dive into the story of my fathers mothers, Joyce and Edith:

My paternal grandmother Joyce was just fifteen when she gave birth to my father. She was an Irish immigrant in the UK, working as kitchen staff in a house in Kent in 1940. Then when it was discovered she was pregnant, she was sent to a place where they put girls who got themselves in ‘trouble’, a place designed to relieve young women of their ‘accidents’ — war babies. These girls and women went to full term and then their babies were sent away for adoption.

After the birth and the adoption, young Joyce disappears without trace. We do not know where she went. Did she leave the country? Nobody knows. My father looked for her throughout his life. My mother has told me that my father was convinced that Joyce had committed suicide and perhaps this was a factor that triggered his own demise.

I have often wondered where Joyce went. What happened to that teenager who was my fifteen year old Irish grandmother? I wonder what she looked like? I wonder if I have her Irish green-gold eyes and if I’m like her at all. I always hoped she survived and lived well.

I was brought up by my Jamaican mother and grandmother, and so I know the similarities I inherited from both of them, but I do not know my other parts. I can romanticise it a little bit, perhaps my Irish blood is the times when I surprise myself, when I am impulsive, when I’m like a girl made of lightening, when I can be reckless, careless, that seems to be in line with my father’s traits. When I’m cautious and thoughtful, perhaps that’s my mother’s calm influence.

image: black and white family photo, The Heart of Springfield Road, my grandmother Edith, my fathers mother

I hope Joyce had the fire I seem to have. I must have got it from somewhere. I like to imagine she changed her name and ran away to enjoy her freedom and a beautiful life. Wherever Joyce went, the truth of my father’s Irish bloodline went with her. And the fact remains that Edith Godden, pictured above, the midwife to his birth, took him home and was the sole parent to my five-month young father. Edith gave him her name, Godden, and she loved him and cared for him and brought him up alone and as her own.

Tragically Edith was killed one Christmastime. She died in a car accident when I was a baby. She was knocked over right by our home, at the top of Springfield Road by a drunk driver. So I never knew her and couldn't ask her all of these questions, but I do know that Edith was adored, that she was generous with her heart. I have a battered old suitcase once belonging to my grandfather George and in it I found a stack of cards and letters of condolence, tied with ribbons, postmarked December 1972.

And so here then is a tale of women, of vanishings and erasure, of sisterhood, of the trail our elders blaze for us, of women supporting women. When people ask me where I come from, I wish I could tell them this story. I come from incredible women, I want to reply, I come from sea and salt and flame and heart, I want to say, I come from the fearless spirit of leading with love. Sometimes perhaps it is not so much about where on a man-made map you come from in this vicious and messy world, but who you come from and I love who I came from. I have a deep love and respect for my mother and grandmothers. I know I come from a lineage of quiet courage, of resilience and patience and care. I know the events of their lives and the choices they made altered mine. I know I wouldn’t be here writing books and having the guts to work at it and try, try, try, again, if it was not for them.

So many years have passed, yet we still don't know where Joyce went and how come it was that nurse Edith adopted my dad and took him home with her. However, as I write all of this today it must be to remind us that we are here and now because they were there and then and as long as I remember these women and sing their names, they are celebrated and alive in me and in my work. I share my love and gratitude in this way. This is the heart of my work, the heart of my fire, the heart of my …. everything.

image: black and white photo, my grandmother Muriel, my mothers mother

The Heart Of Springfield Road

excerpt from ‘Springfield Road - A Poets Childhood Revisited’

If the heart of the home is the kitchen, then it is the soul that rules that kitchen that makes that heart beat. At Springfield Road, this was Edith Godden, my paternal grandmother and Grandpa George’s wife.

Edith Godden: in every one of the old black and white photographs you could see the good shining inside her. She loved children; in photos she was most often holding a child. She had ruddy cheeks, her white hair a wild mess. She always wore her apron. She was all bosom, with baggy stockings and capable-looking hands. I always pictured her with arms full of clean linen, folded to put away upstairs in one of the rosewood, mothballed drawers in the upstairs bedrooms. Clothes pegs still attached, clipped to the front of her pinny pocket. Hastings is forever the archetypal British seaside holiday resort that needs a holiday, all faded grandeur and peeling façade. So too was the house on Springfield Road, with the walls still echoing a time when it was full of life, laughter and love. There was a time when the bricks of the house vibrated with the laughter and tears of dozens of children who were taken in or fostered here over the years, like my dad Paul and Uncle Peter and other people who were homeless: refugees or immigrants seeking shelter. This was a house for the lost and found. Everyone who came here, it seemed, came looking for something; everyone who came here had lost pieces of the jigsaw. I imagine Edith being run off her feet but loving every minute, bossing people about, ordering and organising chaotic bath times according to limits of hot water. Most of all, I liked to imagine lovely cramped tea-times with too many at the table. A slather of jam and toasted crumpets. Edith probably never sat down but hovered and fussed with a crumpled tea towel in her hand.

Edith Josephine Godden was born in September in 1906 at home on Beaconsfield Road in Dover, the daughter of a submarine diver. She was a district nurse in the war. In 1930 she completed her nurse’s training at Connaught Hospital for Walthamstow, Wanstead and Leyton, then went on to work in a convalescent home in Bearstead, Kent. Whatever else went on there, it was a place where they sent girls who had got themselves in ‘trouble’, a place designed to relieve them of their burdens, war babies, their secrets and accidents. These illegitimate bundles were then put up for adoption and sent to orphanages until, it was hoped, they found good homes.

On 24 April 1941, a baby boy was born to a teenage Irish girl named Joyce Tremlett. This newborn baby was my father, Paul. We will never know what it was Edith Godden saw in this baby; for all the children she helped to bring into the world as a district maternity nurse, she didn’t adopt any others. Perhaps a ray of sunshine lit the room as he entered the world and something inside Edith was moved. Perhaps she saw him in a dream the night before, or in the tea leaves in her cup. I love to imagine she shared a special bond with the teen mother, Joyce, who was as young as only fifteen and may have been alone here in England. I have imagined that her Irish family didn’t know about her predicament. Or that they found out and disowned her with a Catholic washing of hands. Either way, to me, it is not that difficult to picture Edith, then aged thirty-five, unwed and without a child of her own, seeing before her a young frightened Irish girl with a baby and nowhere bright for either mother or child to go. I have indulged in a scene of the two of them together, Edith and Joyce.

It is spring, a crisp late April morning. The daffodils and crocuses have burst through the grass outside and below the windows of a white, sanitised room. I see a trembling Joyce, my real grandmother, as a teenager. I see her big round eyes, the same eyes as my father’s and mine, sea-green-blue, all welling up with tears. I see the two women holding hands. Tears trickle down Joyce’s face and I see Edith holding her hand as Joyce might have asked in her Irish accent, You’ll take good care of him, won’t you?

In reality, I imagine Joyce probably had very little control over her destiny and that of her illegitimate son. It is a fact that the case went to juvenile court, though. Filling in the gaps in what I have been told or overheard, the real story goes a little more like this:

It is 1940. We have a teenage Joyce over from Ireland, working as a scullery or kitchen maid for a rich Kent family. She is ‘seduced’ by her boss, an anonymous older wealthy gentleman. She falls pregnant and is sent to a home in Bearstead, Kent, to have the baby, and this is where Edith Godden steps in and saves the day. Now, I have so many feelings about these two women. Sadness for Joyce and her loss, the fifteen-year-old Irish girl forced to see her pregnancy to full term only to have the baby given away or taken from her.

I feel relief and gratitude that I know Edith was kind and good. It is a story of women making the best of a situation in a system that did not properly protect women’s rights. It is a story of courage and survival and I know I am only here now because they were so strong.

It’s highly likely my unnamed paternal grand-father, was an older, married man, affluent, with a large house. He had power and a property big enough to still warrant staff during the Second World War, when rations were scarce and for most people luxuries such as servants had been forsworn. He kept his identity secret and his hands nice and clean. After the birth and adoption of my father, Joyce disappears from the records without trace. Did she go home to Ireland? Did she run away in pursuit of a new identity? Did she go somewhere far away like America or Australia? Was she committed to an asylum or hospital? Did she live or did she die? Nobody seems to know. My father longed for the truth of it; he looked for her sporadically throughout his life and always came up empty-handed.My mother has told me that my father was convinced Joyce had committed suicide, and that the not knowing, the fruitless searches, that pained him deeply. It is unfinished business, a gaping hole in the material of who on this earth you are really made of. Who made you? Wherever Joyce went, the truth of my father’s birth and his true Irish ancestry went with her. But another truth remains: the adoption papers plainly state that as of 22 August 1941 Edith Godden was the sole parent to my five-month-old father, and that from then on he was known as Paul Godden.

And so here is the beginning of the story, another beginning…

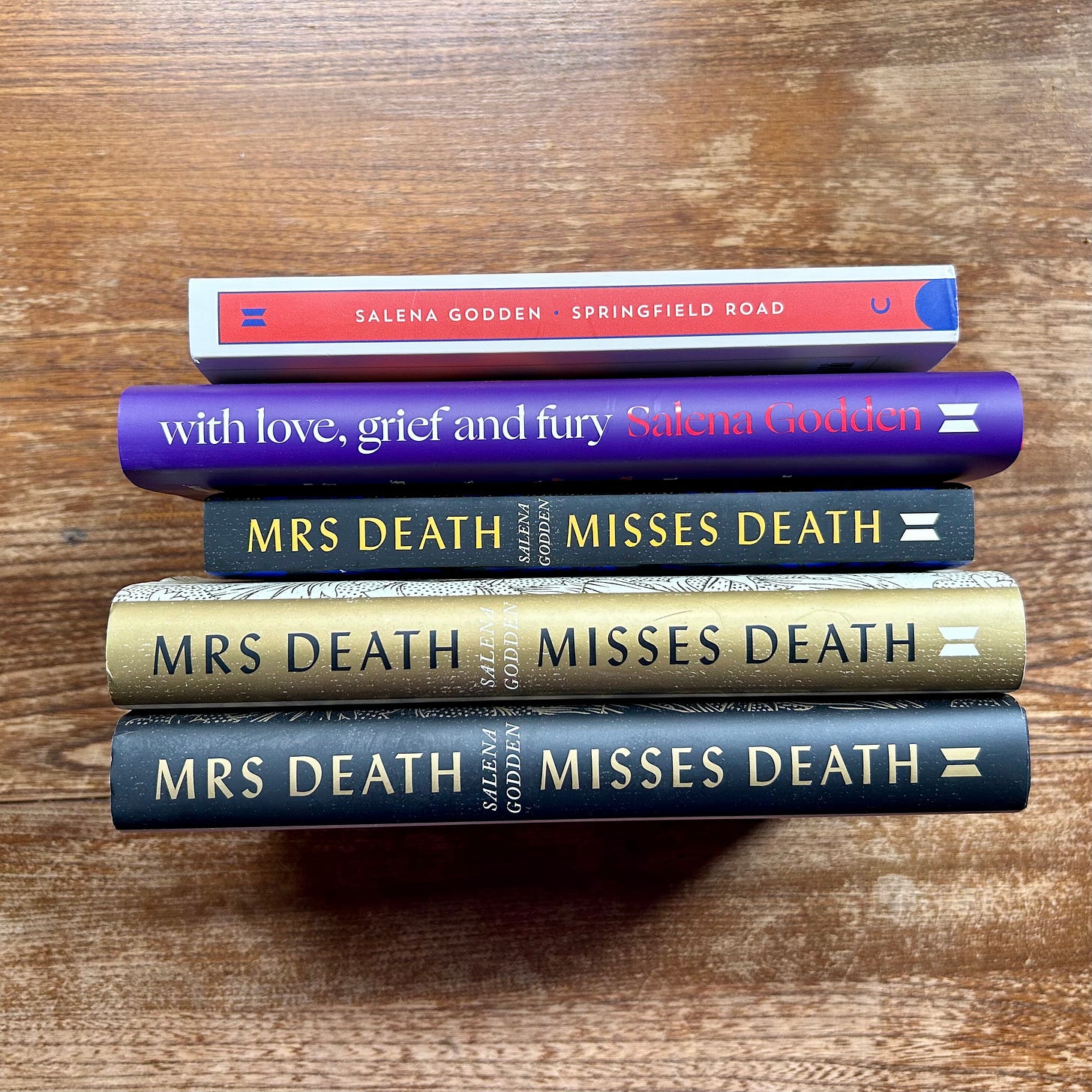

Literary memoir ‘Springfield Road - A Poets Childhood Revisited’ is out now in paperback alongside a new poetry collection ‘With Love, Grief and Fury’ and award-winning debut novel ‘Mrs Death Misses Death’ out now in print, ebook and audio, published by Canongate Books

Thank you for reading this far down the page.

Coming up I have these three amazing festivals:

I’m doing a solo performance at Green Gathering on Saturday August 3rd. Then I’ll be up in Scotland to do lots of talks and events at Edinburgh International Book Festival, roughly August 9th - 13th. I head home for Hastings Book Festival in September, where I will be in conversation about books and more with my elegant and beautiful friend Anita Rani.

I’ll leave you with this pic from last summer, Green Gathering 2023. I cannot wait to return there this weekend, over the last decade or so I have performed there almost every summer. I highly recommend it. It is one of the cleanest and greenest festivals in Europe, the original off-grid, non-profit festival powered by sun and wind. It is such an inspirational and happy four days. I look forward to sharing my new books and poems in fields of summer hay and cider joys, see you here and there,

Keep on keeping on my lovelies...

BIGlove, Xxsg

Poetry. Books. Gigs.

Out now: With Love, Grief and Fury

Out now: Springfield Road

Out now: Pessimism is for Lightweights

Out now: Mrs Death Misses Death

Linktree: https://linktr.ee/salenagodden

" Sometimes perhaps it is not so much about where on a man-made map you come from in this vicious and messy world, but who you come from and I love who I came from. " I love this! Don't know whether you've seen this video of Leah Manaema talking about indigeneity - I've watched it about a dozen times, there's so much good in there - but in particular, it got me thinking about bloodlines and ancestors, and wishing that we used indigenous ways of introducing ourselves instead of the old "what do you do?"

https://www.instagram.com/reel/C5-mL_nR63v/